2012-07. Accumulation by Dispossession: Barrick & Goldcorp’s Pueblo Viejo Gold Mine in the Dominican Republic

Cotuí. Sánchez Ramírez, Dominican Republic.

July 30th, 2012.

Issues: Mining / Land Tenure / Impunity

Barrick and Goldcorp’s Pueblo Viejo gold mining project, the “biggest single foreign direct investment ever done in the Dominican Republic estimated at US $3.5 billion”, should begin full operations in July 2012. While the economic sectors deem it an economic blessing, the local population, environmentalists, and progressive groups strongly oppose it due to numerous social problems already underway and the potential to cause an irreversible environmental disaster in the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. (1)

Barrick and Goldcorp’s Pueblo Viejo gold mining project, the “biggest single foreign direct investment ever done in the Dominican Republic estimated at US $3.5 billion”, should begin full operations in July 2012. While the economic sectors deem it an economic blessing, the local population, environmentalists, and progressive groups strongly oppose it due to numerous social problems already underway and the potential to cause an irreversible environmental disaster in the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. (1)

MiMundo.org spent the month of April 2012 documenting the impact of the Pueblo Viejo project on both local and national scales. Using Google Earth, MiMundo.org prepared this map of the region adding rough placements for the local communities, the under-construction El Llagal tailings pond, in addition to other reference points. Images in the photo essay will refer back to this map in order to help understand the massive impact of the mining project.

MiMundo.org spent the month of April 2012 documenting the impact of the Pueblo Viejo project on both local and national scales. Using Google Earth, MiMundo.org prepared this map of the region adding rough placements for the local communities, the under-construction El Llagal tailings pond, in addition to other reference points. Images in the photo essay will refer back to this map in order to help understand the massive impact of the mining project.

Note: the map runs North-South from left to right, and East-West from top to bottom.

Pueblo Viejo: From its beginnings to the Barrick-Goldcorp era

“The first concession for commercial exploitation of Pueblo Viejo was given in 1972 to the New York and Honduras Rosario Mining Company. It was to exploit gold, silver, zinc and copper from 752 hectares in an open-pit mine.” The local subsidiary, Rosario Dominicana, S. A. exploited Pueblo Viejo from 1975 until 1999. “The operations of Rosario Dominicana were disastrous in environmental, social and financial terms. At least four rivers of the area were polluted with Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) and with discharges from the tailings dams, one of which overflowed in 1979 during a hurricane; and more than 600 families were displaced [to make way for the project].” (2)

“The first concession for commercial exploitation of Pueblo Viejo was given in 1972 to the New York and Honduras Rosario Mining Company. It was to exploit gold, silver, zinc and copper from 752 hectares in an open-pit mine.” The local subsidiary, Rosario Dominicana, S. A. exploited Pueblo Viejo from 1975 until 1999. “The operations of Rosario Dominicana were disastrous in environmental, social and financial terms. At least four rivers of the area were polluted with Acid Mine Drainage (AMD) and with discharges from the tailings dams, one of which overflowed in 1979 during a hurricane; and more than 600 families were displaced [to make way for the project].” (2)

Pictured: The Pueblo Viejo project seen northeast from the Cerro del Chivo peak.

“In addition, the company’s interest in short-term profit led to a lack of strategic planning, focusing on the extraction of the upper layer of oxides, which constituted only a small portion of the mineral reserves. When the upper oxides were depleted, Rosario Dominicana found itself without the technology to exploit the remaining transitional and sulphide ores; unable to make the capital investment, in addition to unfavorable market metal prices, the project closed permanently in 1999, leaving an environmental disaster whose clean-up cost was estimated in between US$100 and US$200 million in 2001.” (3)

“In addition, the company’s interest in short-term profit led to a lack of strategic planning, focusing on the extraction of the upper layer of oxides, which constituted only a small portion of the mineral reserves. When the upper oxides were depleted, Rosario Dominicana found itself without the technology to exploit the remaining transitional and sulphide ores; unable to make the capital investment, in addition to unfavorable market metal prices, the project closed permanently in 1999, leaving an environmental disaster whose clean-up cost was estimated in between US$100 and US$200 million in 2001.” (3)

Pictured: Open-pit benches, mostly leftover from the Rosario Dominicana days. Looking north from the Cerro del Chivo peak.

Without carrying out any clean-up procedures, Canadian Placer Dome was issued a new exploitation license in 2003 for Pueblo Viejo. In 2006, Canadian mining giant Barrick, the World’s largest gold producer, acquired Placer Dome. That same year, another Canadian mining heavyweight, Goldcorp, acquired 40% stake in the renewed Pueblo Viejo project, even though Barrick continues as the sole operator through its local subsidiary Pueblo Viejo Dominicana Corporation (PVDC). “With the Barrick acquisition, the scope of the project increased, from the original US $336 million investment planned by Placer Dome it grew to an approximately US $3.5 billion investment.” (4)

Without carrying out any clean-up procedures, Canadian Placer Dome was issued a new exploitation license in 2003 for Pueblo Viejo. In 2006, Canadian mining giant Barrick, the World’s largest gold producer, acquired Placer Dome. That same year, another Canadian mining heavyweight, Goldcorp, acquired 40% stake in the renewed Pueblo Viejo project, even though Barrick continues as the sole operator through its local subsidiary Pueblo Viejo Dominicana Corporation (PVDC). “With the Barrick acquisition, the scope of the project increased, from the original US $336 million investment planned by Placer Dome it grew to an approximately US $3.5 billion investment.” (4)

Pictured: Carbon in Leach (CIL) Tanks where the gold particles are recovered after using cyanide to dislodge them from the ore. Looking east from the Cerro del Chivo peak.

Natalio Gálvez Santo, 17, from La Cerca, rides a horse on the ridge of Cerro del Chivo. Looking south-southeast from the Cerro del Chivo peak, the massive El Llagal tailings pond is under development on the Southside of Highway 17.

Natalio Gálvez Santo, 17, from La Cerca, rides a horse on the ridge of Cerro del Chivo. Looking south-southeast from the Cerro del Chivo peak, the massive El Llagal tailings pond is under development on the Southside of Highway 17.

Squeezed Out: the Surrounding Community of La Cerca

Over the years, the communities of La Cerca and Las Lagunas have developed along Highway 17. Today, they literally find themselves sandwiched-in by the Pueblo Viejo open pit to the North and the El Llagal tailings pond to the South. Pictured is a South to North view of the eastern section of La Cerca, as seen from Vista 2 viewpoint on the map.

Over the years, the communities of La Cerca and Las Lagunas have developed along Highway 17. Today, they literally find themselves sandwiched-in by the Pueblo Viejo open pit to the North and the El Llagal tailings pond to the South. Pictured is a South to North view of the eastern section of La Cerca, as seen from Vista 2 viewpoint on the map.

An opposite North to South view of the eastern end of La Cerca, as viewed from the Cerro del Chivo peak, reveals the community’s fragile location under the El Llagal tailings pond. “Already in May 2011, dozens of families of surrounding communities and thousands of PVDC workers had to be temporarily evicted due to the risk of the [El Llagal] dam collapsing because of the record amount of sudden rains registered in the area. In that case the risk was of water sweeping away houses and farming fills; once the dam is filled with tailings, it would be toxic waste that would risk spilling.” (5)

An opposite North to South view of the eastern end of La Cerca, as viewed from the Cerro del Chivo peak, reveals the community’s fragile location under the El Llagal tailings pond. “Already in May 2011, dozens of families of surrounding communities and thousands of PVDC workers had to be temporarily evicted due to the risk of the [El Llagal] dam collapsing because of the record amount of sudden rains registered in the area. In that case the risk was of water sweeping away houses and farming fills; once the dam is filled with tailings, it would be toxic waste that would risk spilling.” (5)

Local residents of Pueblo Viejo’s adjacent communities, particularly La Cerca, currently face a serious risk of losing their territories, either through an industrial accident or by being forced out by the massively encroaching mining project.

Local residents of Pueblo Viejo’s adjacent communities, particularly La Cerca, currently face a serious risk of losing their territories, either through an industrial accident or by being forced out by the massively encroaching mining project.

Having already lived through nearly 30 years of a messy and conflictive extractive process from the Rosario Dominicana days, locals are aware this new massive mine will not solve their pressing issues. “After 24 years of mining operations [where] 5.5 million ounces (Moz) of gold and 24.4 Moz of silver [were] produced, poverty and unemployment are still high in the communities of the surrounding, many of which lack potable water, energy, sewage system, and suffer from low levels of literacy.” (6)

Having already lived through nearly 30 years of a messy and conflictive extractive process from the Rosario Dominicana days, locals are aware this new massive mine will not solve their pressing issues. “After 24 years of mining operations [where] 5.5 million ounces (Moz) of gold and 24.4 Moz of silver [were] produced, poverty and unemployment are still high in the communities of the surrounding, many of which lack potable water, energy, sewage system, and suffer from low levels of literacy.” (6)

Pictured: A toddler from the eastern end of La Cerca.

Rosamaría Belén, resident of the eastern end of La Cerca, carries home a bucket of water from a communal tap.

Rosamaría Belén, resident of the eastern end of La Cerca, carries home a bucket of water from a communal tap.

A local woman from the eastern end of La Cerca collects dry laundry from a tin rooftop.

A local woman from the eastern end of La Cerca collects dry laundry from a tin rooftop.

Rooftop view of the eastern end of La Cerca and El Llagal tailings pond in the background.

Rooftop view of the eastern end of La Cerca and El Llagal tailings pond in the background.

Despite constant explosions, excavations and non-stop machinery at work nearby, residents of La Cerca refuse to sell their lands.

Despite constant explosions, excavations and non-stop machinery at work nearby, residents of La Cerca refuse to sell their lands.

La Cerca Community elder Juliana Guzman reiterates the situation: “My family was already relocated from a community that no longer exists [during the time of Rosario Dominicana]. I am too old to move again. This is my land and I intend to stay.”

La Cerca Community elder Juliana Guzman reiterates the situation: “My family was already relocated from a community that no longer exists [during the time of Rosario Dominicana]. I am too old to move again. This is my land and I intend to stay.”

Antia Ferrera Lasala, from La Cerca, prepares rice. The grain is the Dominican Republic’s staple food and large part of the country’s rice fields are in the Cibao Valley, downstream from the mine.

Antia Ferrera Lasala, from La Cerca, prepares rice. The grain is the Dominican Republic’s staple food and large part of the country’s rice fields are in the Cibao Valley, downstream from the mine.

Local families primarily depend on the cultivation of cacao and the sale of their respective cocoa beans. Trees that have stood for generations continue to produce cacao pods year-round in this extraordinarily fertile region of the Dominican Cibao.

Local families primarily depend on the cultivation of cacao and the sale of their respective cocoa beans. Trees that have stood for generations continue to produce cacao pods year-round in this extraordinarily fertile region of the Dominican Cibao.

Juan Toribio (left) and Ludovino Fernández, residents of La Cerca and members of the Cacao Producers Association from the Department of Sánchez Ramírez – Cotuí Chapter, claim production has steadily dropped in recent years due to increased dust from the mine that damages the cacao pods.

Juan Toribio (left) and Ludovino Fernández, residents of La Cerca and members of the Cacao Producers Association from the Department of Sánchez Ramírez – Cotuí Chapter, claim production has steadily dropped in recent years due to increased dust from the mine that damages the cacao pods.

Ludovino Fernández holds cacao pods that have rotted too quickly. Locals are convinced it is due to contamination from the nearby Pueblo Viejo mine, located literally on the other side of the hill.

Ludovino Fernández holds cacao pods that have rotted too quickly. Locals are convinced it is due to contamination from the nearby Pueblo Viejo mine, located literally on the other side of the hill.

As it tends to occur in communities adjacent to industrial mining projects that carry out constant detonations and tunnel perforations, large cracks are beginning to appear in numerous structures, particularly homes.

As it tends to occur in communities adjacent to industrial mining projects that carry out constant detonations and tunnel perforations, large cracks are beginning to appear in numerous structures, particularly homes.

A large crack splits open the middle wall of Tomasina Dislagómez’s two-room home in the western end of La Cerca.

A large crack splits open the middle wall of Tomasina Dislagómez’s two-room home in the western end of La Cerca.

The headquarters for the Cotuí Chapter of the Cacao Producers Association from the Department of Sánchez Ramírez has suffered significant damage.

The headquarters for the Cotuí Chapter of the Cacao Producers Association from the Department of Sánchez Ramírez has suffered significant damage.

Intra-community Conflicts: Las Lagunas Hamlet

Like La Cerca, the community of Las Lagunas lays directly along Highway 17 between the main industrial complex and El Llagal tailings pond. The name of the community, which split from La Cerca a few decades ago, comes from its proximity to these toxic lagoons, or tailings ponds, leftover from the Rosario Dominicana era (view due east from Cerro del Chivo peak).

Like La Cerca, the community of Las Lagunas lays directly along Highway 17 between the main industrial complex and El Llagal tailings pond. The name of the community, which split from La Cerca a few decades ago, comes from its proximity to these toxic lagoons, or tailings ponds, leftover from the Rosario Dominicana era (view due east from Cerro del Chivo peak).

Gonzalo Yepes Martínez, from Las Lagunas, explains that the small roadside community is made up of a dozen or so households all related to each other. As an active member of the Cacao Producers Association, he firmly opposes the mining project and worries about his family’s health, economic wellbeing, and outright capacity to continue living in their homes. Nevertheless, serious interfamily rifts have occurred as several of his kin either work for PVDC or have setup small eatery joints frequented by the company’s employees. Due to the intra-communal conflicts and damages to his home, Gonzalo and his family primarily reside in Cotuí now.

Gonzalo Yepes Martínez, from Las Lagunas, explains that the small roadside community is made up of a dozen or so households all related to each other. As an active member of the Cacao Producers Association, he firmly opposes the mining project and worries about his family’s health, economic wellbeing, and outright capacity to continue living in their homes. Nevertheless, serious interfamily rifts have occurred as several of his kin either work for PVDC or have setup small eatery joints frequented by the company’s employees. Due to the intra-communal conflicts and damages to his home, Gonzalo and his family primarily reside in Cotuí now.

A woman from Las Lagunas dries laundry as the El Llagal tailings pond sits only a couple hundred meters behind. Many homes have suffered damages in Las Lagunas, but access to photograph was difficult to achieve.

A woman from Las Lagunas dries laundry as the El Llagal tailings pond sits only a couple hundred meters behind. Many homes have suffered damages in Las Lagunas, but access to photograph was difficult to achieve.

Deceptions and Land Disputes: The Nuevo Llagal Community

In order to make way for the massive El Llagal tailings pond, hundreds of families who made up the communities of El Llagal, Fátima and Los Cacaos were relocated roughly 9 km west to an orderly, urbanized community aptly named El Nuevo Llagal (The New Llagal), on the outskirts of the city of Maimón.

In order to make way for the massive El Llagal tailings pond, hundreds of families who made up the communities of El Llagal, Fátima and Los Cacaos were relocated roughly 9 km west to an orderly, urbanized community aptly named El Nuevo Llagal (The New Llagal), on the outskirts of the city of Maimón.

José Agustín Gálvez, President of the Neighbors Committee of Nuevo Llagal, states: “We have had some serious non-compliance issues by Barrick since we were evicted in 2008 from our original communities. No jobs have been given to us as were promised, nor has the company given us the land with cocoa trees that was also part of the deal. We had very fertile trees there and here, even though we live in what seem nicer homes, we have no jobs nor do we have land to cultivate. What are we to do?!”

José Agustín Gálvez, President of the Neighbors Committee of Nuevo Llagal, states: “We have had some serious non-compliance issues by Barrick since we were evicted in 2008 from our original communities. No jobs have been given to us as were promised, nor has the company given us the land with cocoa trees that was also part of the deal. We had very fertile trees there and here, even though we live in what seem nicer homes, we have no jobs nor do we have land to cultivate. What are we to do?!”

In addition, many Nuevo Llagal locals are also utterly disgruntled as they were coerced to sell their tareas (equivalent to 628.86 squared meters) at RD $8,600 [US $200] to the government, while this latter entity sold the same terrains to Barrick for US $28,000. (7)

Genaro Aquino Correa, mayor of Nuevo Llagal and former resident of El Llagal, states: “Our struggle is clear: we want the company to honor their part of the deal. We want them to pay us what they owe us and to give us arable land as good as what we once had. That was their promise.”

Genaro Aquino Correa, mayor of Nuevo Llagal and former resident of El Llagal, states: “Our struggle is clear: we want the company to honor their part of the deal. We want them to pay us what they owe us and to give us arable land as good as what we once had. That was their promise.”

As locals from Nuevo Llagal have been at the forefront of the protest movement against Barrick and Goldcorp’s PVDC, repression has followed. In late April 2012, roughly a dozen armed troops have permanently occupied the Nuevo Llagal community center in a clear act of intimidation that also keeps locals from meeting. (8)

Regional and National Impact of Pueblo Viejo

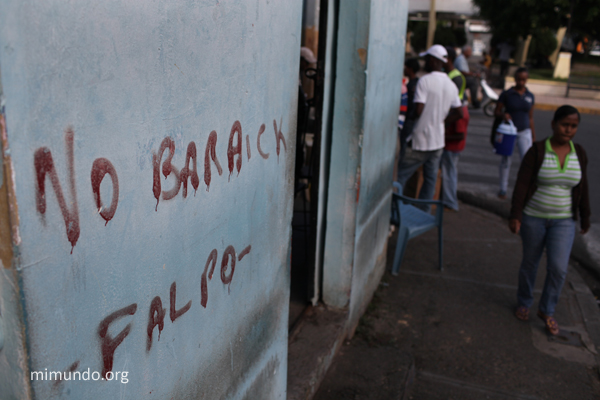

Fifteen km north of the mine, in the regional hub of Cotuí, graffiti near the central park signed by the Frente Amplio de Lucha Popular (FALPO, or Broad Front for Popular Struggle) reads: “No Barrick.”

Fifteen km north of the mine, in the regional hub of Cotuí, graffiti near the central park signed by the Frente Amplio de Lucha Popular (FALPO, or Broad Front for Popular Struggle) reads: “No Barrick.”

One of the clearest arguments against the Pueblo Viejo project is based on its proximity to the colossal Hatillo Dam, perhaps the country’s most important freshwater source. Measuring 22 square kilometers, the dam irrigates the Cibao’s rice fields, the country’s main staple food, as well as numerous other crops both for national consumption and export.

One of the clearest arguments against the Pueblo Viejo project is based on its proximity to the colossal Hatillo Dam, perhaps the country’s most important freshwater source. Measuring 22 square kilometers, the dam irrigates the Cibao’s rice fields, the country’s main staple food, as well as numerous other crops both for national consumption and export.

The 210-km-long Yuna River fills the Hatillo Dam between the cities of Maimón and Cutuí before continuing its flow out into the fertile Eastern Cibao Valley. A collapse of the toxic El Llagal tailings pond would quickly contaminate both the island’s most plentiful river and the largest freshwater reservoir. (9)

The 210-km-long Yuna River fills the Hatillo Dam between the cities of Maimón and Cutuí before continuing its flow out into the fertile Eastern Cibao Valley. A collapse of the toxic El Llagal tailings pond would quickly contaminate both the island’s most plentiful river and the largest freshwater reservoir. (9)

“The company assures that it follows the highest standards of security, but as past experiences have shown, tailing breaches have occurred in countries with a much stronger tradition of organization, discipline and monitoring than DR, and in mining companies that also claim to follow best possible practices (such as Newmont cyanide spill in Ghana in 2009). Moreover, at least one Dominican engineer has publicly stated that El Llagal dam has serious technical failures.” (10)

“The company assures that it follows the highest standards of security, but as past experiences have shown, tailing breaches have occurred in countries with a much stronger tradition of organization, discipline and monitoring than DR, and in mining companies that also claim to follow best possible practices (such as Newmont cyanide spill in Ghana in 2009). Moreover, at least one Dominican engineer has publicly stated that El Llagal dam has serious technical failures.” (10)

Pictured: El Llagal tailings pond as seen from Vista 2.

Pineapple distributor delivers to a street side fruit vendor of Cotuí. Many of these pineapples come from the adjacent communities to the Pueblo Viejo project.

Pineapple distributor delivers to a street side fruit vendor of Cotuí. Many of these pineapples come from the adjacent communities to the Pueblo Viejo project.

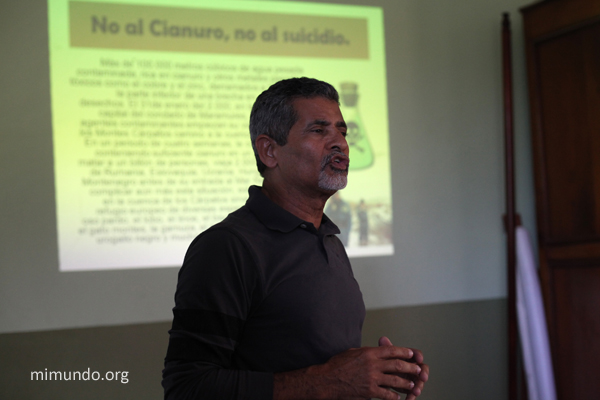

Domingo Abreu, director of the Asamblea Nacional Ambiental (ANA, or National Environmental Assembly), gives a lecture at a local school in Cotuí regarding the dangers of industrial mining. The slide behind him reads: “No to cyanide, no to suicide.” Despite being based in Santo Domingo, Mr. Abreu and other ANA collaborators constantly lecture around the country on the negative impacts of open-pit mining.

Domingo Abreu, director of the Asamblea Nacional Ambiental (ANA, or National Environmental Assembly), gives a lecture at a local school in Cotuí regarding the dangers of industrial mining. The slide behind him reads: “No to cyanide, no to suicide.” Despite being based in Santo Domingo, Mr. Abreu and other ANA collaborators constantly lecture around the country on the negative impacts of open-pit mining.

Prior to the May 2012 Presidential elections, well-known entrepreneur Ignacio Joga ran a presidential campaign primarily on an anti-Barrick platform using the slogan “The People demand: Out with Barrick Gold!” Joga’s run for the presidency with the Partido de los Dominicanos (PDD, or Party for the Dominicans) ultimately failed. Nevertheless, Joga’s anti-Barrick platform demonstrates how the industrial project clearly attracts nationwide attention.

Prior to the May 2012 Presidential elections, well-known entrepreneur Ignacio Joga ran a presidential campaign primarily on an anti-Barrick platform using the slogan “The People demand: Out with Barrick Gold!” Joga’s run for the presidency with the Partido de los Dominicanos (PDD, or Party for the Dominicans) ultimately failed. Nevertheless, Joga’s anti-Barrick platform demonstrates how the industrial project clearly attracts nationwide attention.

More graffiti in Cotuí reads: “No Barrick Gold!”

More graffiti in Cotuí reads: “No Barrick Gold!”

Dispossession, Accumulation, and Resistance

“Dispossession is found at the center of industrial mining activities. Just like other industries in the natural resources sector, mining investments cannot proceed without dispossessing a community – usually an indigenous one – from its land, its resources, and its way of life.” (11)

“Dispossession is found at the center of industrial mining activities. Just like other industries in the natural resources sector, mining investments cannot proceed without dispossessing a community – usually an indigenous one – from its land, its resources, and its way of life.” (11)

“Gold mining in particular tends to have a greater impact than any other type of mining, with Western gold mining companies having a dark record of toxic pollution and destruction of natural reserves on their operations around the world.” (12)

“Gold mining in particular tends to have a greater impact than any other type of mining, with Western gold mining companies having a dark record of toxic pollution and destruction of natural reserves on their operations around the world.” (12)

Pictured: Odalisi Toribio, 19, from La Cerca, holds her three-month old daughter Marisol.

“Since only 11 percent of gold is used for industrial purposes and the rest is used as investment and jewelry, gold mining could be considered an unnecessary activity.” (13)

“Since only 11 percent of gold is used for industrial purposes and the rest is used as investment and jewelry, gold mining could be considered an unnecessary activity.” (13)

Pictured: Apolinar Guzman (left), cacao producer from La Cerca, eats breakfast with his sister-in-law Mercedes Suárez Gálvez.

“Nearly 100 million people have been displaced worldwide from their lands in the past one hundred years due to mining projects, either by violent methods or receiving barely minimal compensation.” (14)

“Nearly 100 million people have been displaced worldwide from their lands in the past one hundred years due to mining projects, either by violent methods or receiving barely minimal compensation.” (14)

Pictured: Flora Ovalle, from the eastern end of La Cerca, collects laundry outside her home.

“Striking a Better Balance, the final report of the Extractive Industries Review (EIR) – an independent consultation launched by the World Bank in 2001 – recognized that, contrary to the World Bank’s own arguments, investment in mining has often constituted a further threat to the poor and the environment, and has been linked to human rights abuses and civil conflict.” (15)

“Striking a Better Balance, the final report of the Extractive Industries Review (EIR) – an independent consultation launched by the World Bank in 2001 – recognized that, contrary to the World Bank’s own arguments, investment in mining has often constituted a further threat to the poor and the environment, and has been linked to human rights abuses and civil conflict.” (15)

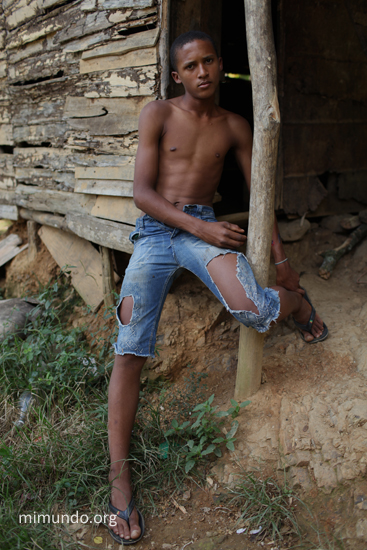

Pictured: Marcelino Gálvez Suárez, 17, from La Cerca, sits outside his home.

“The current exploitation of Pueblo Viejo responds to the needs of transnational capitalism, embodied by multinational corporations, and can be understood as an example of the permanent accumulation by dispossession, as explained by David Harvey, a common characteristic of capitalist development.” (16)

“The current exploitation of Pueblo Viejo responds to the needs of transnational capitalism, embodied by multinational corporations, and can be understood as an example of the permanent accumulation by dispossession, as explained by David Harvey, a common characteristic of capitalist development.” (16)

Pictured: A home in the eastern end of La Cerca with a plastic flag of the Dominican Republic, with El Llagal tailings pond in the background.

“It is only the mass struggle of the poor, workers and indigenous people of Latin America that will stop the predatory practices of Canadian mining companies.” (17)

“It is only the mass struggle of the poor, workers and indigenous people of Latin America that will stop the predatory practices of Canadian mining companies.” (17)

Pictured: Pedro Ignacio Guzman (center in red) oversees the construction of a new home in the eastern end of La Cerca. Despite the community’s bleak future, locals refuse to sell their lands. “This is our land, and we will stay,” states Guzman.

Juan Toribio Marte, 49, from La Cerca, helps braid his daughter Maribel’s hair. From 2005 to 2011, Toribio Marte worked for PVDC’s Environmental Renovation department. He states: “After working for several years, I realized that what they are doing up there is a great danger to us all down here. I quit in 2011 because I feel it is more important to help save our community than provide services to the foreigners. I neither want my family nor my neighbors to suffer any ailments.”

Juan Toribio Marte, 49, from La Cerca, helps braid his daughter Maribel’s hair. From 2005 to 2011, Toribio Marte worked for PVDC’s Environmental Renovation department. He states: “After working for several years, I realized that what they are doing up there is a great danger to us all down here. I quit in 2011 because I feel it is more important to help save our community than provide services to the foreigners. I neither want my family nor my neighbors to suffer any ailments.”

Ludovino Fernández, from La Cerca, declares: “A hungry or desperate man will turn into a wild beast… Here, the people will eventually rise up.”

Ludovino Fernández, from La Cerca, declares: “A hungry or desperate man will turn into a wild beast… Here, the people will eventually rise up.”

This photo essay was made possible with the support of Mining Watch, ProtestBarrick.net, and Rights Action.

The Salva Tierra collective, ANA, and UASD students in Cotuí provided valuable information and logistical support in the Dominican Republic.

To license the images: Instructions can be found here. The Pueblo Viejo photo gallery is here.

Versión en español aquí.

1 Rodríguez Grullón, Virginia Antares. Tras el Oro de Pueblo Viejo: Del Colonialismo al Neoliberalismo. Un análisis crítico del mayor proyecto minero dominicano. Academia de Ciencias de República Dominicana, 2012. P. 15.

2 Ibid. P. 27.

3 Ibid. Pp. 27-8.

4 Ibid. P. 28.

5 Ibid. P. 38.

6 Ibid. P. 27.

7 Díaz, Wellington. “Campesinos de Cotuí vuelven a reclamar pago tierras donde funciona Barrick.” Hoy. December 6, 2011.

http://www.hoy.com.do/el-pais/2011/12/6/404778/Campesinos-de-Cotui-vuelven-a-reclamar-pago-tierras-donde-funciona-Barrick

8 http://www.accionverde.com/2012/04/24/militares-ocupan-local-comunal-en-el-nuevo-llagal/

9 Op. Cit. Rodríguez Grullón. P. 10.

10 Ibid. Pp. 37-8.

11 Gordon, Todd, & Webber, Jeffrey. “Imperialism and Resistance: Canadian mining companies in Latin America”. Third World Quarterly. Vol 29. 2008. Pp. 67-8.

12 Op. Cit. Rodríguez Grullón. P. 15.

13 Ibid. P. 16.

14 Madeley, John. Big Business, Poor Peoples: The Impact of Transnational Corporations on the World’s Poor. Zed Books; London. 1999.

15 Op. Cit. Rodríguez Grullón. P. 21.

16 Ibid. P. 16.

17 Op. Cit. Gordon & Webber. P. 64.

2 thoughts on “2012-07. Accumulation by Dispossession: Barrick & Goldcorp’s Pueblo Viejo Gold Mine in the Dominican Republic”

Comments are closed.