2007-07. The Chixoy Hydro-Electrical Dam and Genocide in Río Negro

Rabinal. Baja Verapaz, Guatemala.

July 26, 2007.

Issue: Post-War / Historic Memory / Mega-projects

“The Community of Rio Negro, settled along the bank of the Chixoy River, in the municipality of Rabinal, lived off agriculture, fishing, and through the exchange of goods with the neighboring community of Xococ.” (1)“In 1975 the National Institute of Electrification (INDE) presented its plans to build a Hydro-electrical project along the Chixoy River basin, under the patronage of [several international financial institutions such as] the World Bank (WB) and Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).” (2)

“The Community of Rio Negro, settled along the bank of the Chixoy River, in the municipality of Rabinal, lived off agriculture, fishing, and through the exchange of goods with the neighboring community of Xococ.” (1)“In 1975 the National Institute of Electrification (INDE) presented its plans to build a Hydro-electrical project along the Chixoy River basin, under the patronage of [several international financial institutions such as] the World Bank (WB) and Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).” (2)

Nevertheless, community members from Rio Negro refused to leave their territory for several reasons. Besides having never been consulted regarding the mega-project, “the authorities pretended to resettle the population of Rio Negro in Pacux, an arid area, and in housing which did not match their cultural and traditional ways of life.” In addition, the inhabitants of Rio Negro, all belonging to the Maya Achi ethnic group, maintained a certain “attachment to their region” due to millenary traditions. “The Chixoy River basin had been inhabited since the Classic Maya Period (300 BC to 900 AD) by indigenous populations and, besides, a number of religious ceremonial sites still remained.” (3)The image displays the ruins of Kajyub’, a sacred archaeological site on the outskirts of Rabinal City built during the Post-Classic Maya Period (900 AD to 1524 AD). (4)

Nevertheless, community members from Rio Negro refused to leave their territory for several reasons. Besides having never been consulted regarding the mega-project, “the authorities pretended to resettle the population of Rio Negro in Pacux, an arid area, and in housing which did not match their cultural and traditional ways of life.” In addition, the inhabitants of Rio Negro, all belonging to the Maya Achi ethnic group, maintained a certain “attachment to their region” due to millenary traditions. “The Chixoy River basin had been inhabited since the Classic Maya Period (300 BC to 900 AD) by indigenous populations and, besides, a number of religious ceremonial sites still remained.” (3)The image displays the ruins of Kajyub’, a sacred archaeological site on the outskirts of Rabinal City built during the Post-Classic Maya Period (900 AD to 1524 AD). (4) “On March 5th, 1980, two community members of Rio Negro were accused of stealing beans from the Chixoy Dam workers’ mess hall in the town of Pueblo Viejo. They were chased by two soldiers and an agent of the Ambulant Military Police (PMA) all the way to Rio Negro… Once there, a drunken community member hit the PMA Agent who, while trying to protect himself, shot and killed seven inhabitants of Rio Negro. Immediately, community members reacted and beat the agent to death using rocks and machetes. The following day, the Army declared community members as guerrillas, which explained their refusal to leave the territory.” (5)

“On March 5th, 1980, two community members of Rio Negro were accused of stealing beans from the Chixoy Dam workers’ mess hall in the town of Pueblo Viejo. They were chased by two soldiers and an agent of the Ambulant Military Police (PMA) all the way to Rio Negro… Once there, a drunken community member hit the PMA Agent who, while trying to protect himself, shot and killed seven inhabitants of Rio Negro. Immediately, community members reacted and beat the agent to death using rocks and machetes. The following day, the Army declared community members as guerrillas, which explained their refusal to leave the territory.” (5)

“On February of 1982, an armed group, presumably guerrillas, burned down the Xococ market and killed 5 people in the process. Since the Army blamed the guerrillas as well as community members from Rio Negro for the actions, the people of Xococ broke commercial ties with Rio Negro and declared them their enemies.” Afterwards, the Army organized in Xococ a Civil Auto-Defense Patrol (PAC), a paramilitary organization conformed by community members who, “armed, trained, and guided by the Army, would confront the community of Rio Negro as of then.” (7)

“The first action taken by the Xococ PAC was to call a meeting on February 7th, 1982, which congregated 150 community members of Rio Negro under the orders of Rabinal’s military detachment. The leader of the Xococ PAC reprimanded the visitors for belonging to the guerrilla and accused them of burning down the market. Those from Rio Negro denied the accusations, arguing the market benefited them as well and hence had no motive to burn it down.” They were ordered to return to Xococ a week later. “On February 13, 1982, 74 members of Rio Negro (55 men and 19 women) returned to Xococ. Once there, they were executed by the local PAC.” (8)

“The first action taken by the Xococ PAC was to call a meeting on February 7th, 1982, which congregated 150 community members of Rio Negro under the orders of Rabinal’s military detachment. The leader of the Xococ PAC reprimanded the visitors for belonging to the guerrilla and accused them of burning down the market. Those from Rio Negro denied the accusations, arguing the market benefited them as well and hence had no motive to burn it down.” They were ordered to return to Xococ a week later. “On February 13, 1982, 74 members of Rio Negro (55 men and 19 women) returned to Xococ. Once there, they were executed by the local PAC.” (8)

“A month later, on March 13, 1982, around six in the morning, 12 members of the army along with 15 PAC members from Xococ, arrived at the community of Rio Negro… They gathered and forced the population to walk three kilometers uphill. Once at the Pacoxom peak… they proceeded to torture and kill the unarmed victims. Some were hung from the trees, others killed with machetes, while the rest were shot… When the massacre concluded around five in the afternoon, they returned to Xococ. Eighteen surviving children were taken back by the assailants to their community. The testimonies coincide in the number of victims: 177 people (70 women and 107 children), all civil and unarmed community members of Rio Negro.” (9)

“A month later, on March 13, 1982, around six in the morning, 12 members of the army along with 15 PAC members from Xococ, arrived at the community of Rio Negro… They gathered and forced the population to walk three kilometers uphill. Once at the Pacoxom peak… they proceeded to torture and kill the unarmed victims. Some were hung from the trees, others killed with machetes, while the rest were shot… When the massacre concluded around five in the afternoon, they returned to Xococ. Eighteen surviving children were taken back by the assailants to their community. The testimonies coincide in the number of victims: 177 people (70 women and 107 children), all civil and unarmed community members of Rio Negro.” (9)“It is important to highlight the way PAC members were instrumentally forced to participate in the execution of massacres. Besides implicating them in the killings, their use involved a direct method which destroyed the structure of neighboring communities. The Army forced one village to act against a neighboring village.” (10) Today, similar strategies are being used in the forced evictions of indigenous communities (Please see: Canadian Mining Company Orders the Eviction of Indigenous Communities and Barrio La Revolucion Burns).

Jesus Tecu Osorio, who was ten at the time, was one of the eighteen children who survived the massacre carried out on March 13, 1982. His life afterwards, however, turned into a true living nightmare under the orders of PAC member Pedro Gonzales Gomez. In his extraordinary autobiography, Memorial of the Massacres of Rio Negro: Remembrance of my Parents and Memory for my Children, Tecu Osorio recalls: “Soon I became aware that I had become a slave to this PAC member. For over two years, my life only contained suffering, pain and tears… I was a servant to this family.” (11)

Jesus Tecu Osorio, who was ten at the time, was one of the eighteen children who survived the massacre carried out on March 13, 1982. His life afterwards, however, turned into a true living nightmare under the orders of PAC member Pedro Gonzales Gomez. In his extraordinary autobiography, Memorial of the Massacres of Rio Negro: Remembrance of my Parents and Memory for my Children, Tecu Osorio recalls: “Soon I became aware that I had become a slave to this PAC member. For over two years, my life only contained suffering, pain and tears… I was a servant to this family.” (11)Meanwhile, the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank continued to finance the hydro-electric project. “The World Bank actually transferred its second loan installment to the Government of Guatemala in 1985 – three years after the massacres took place… The Chixoy Dam case clearly highlights the complicity of [mentioned] international financial institutions… in the brutal and unlawful displacement of indigenous communities from their land in Guatemala.” (12)

In 1993, before the signing of the Peace Accords, Jesus Tecu Osorio, Carlos Chen (left), and other survivors of Rio Negro organized themselves in order to begin their search for justice and processes involving social, mental, and spiritual reparations. This same year, under constant pressure and serious threats, a series of exhumations of mass graves unearthed hundreds of human remains belonging to former Rio Negro residents. In 1996, the Association for the Integral Development of the Victims of the Violence Maya Achi (ADIVIMA) is formed, while the People’s Legal Clinic emerges in 1998. Currently, the struggle for justice, compensation and reparations related to the Chixoy Dam case continue being led by local activists and organizations of Rabinal.

In 1993, before the signing of the Peace Accords, Jesus Tecu Osorio, Carlos Chen (left), and other survivors of Rio Negro organized themselves in order to begin their search for justice and processes involving social, mental, and spiritual reparations. This same year, under constant pressure and serious threats, a series of exhumations of mass graves unearthed hundreds of human remains belonging to former Rio Negro residents. In 1996, the Association for the Integral Development of the Victims of the Violence Maya Achi (ADIVIMA) is formed, while the People’s Legal Clinic emerges in 1998. Currently, the struggle for justice, compensation and reparations related to the Chixoy Dam case continue being led by local activists and organizations of Rabinal.Graham Russell (right), co-director of Rights Action, translates into English the statements of Carlos Chen. Since 1993, Rights Action has been very much involved in providing financial support to the main processes in Rabinal such as the autobiography of Tecu Osorio, the development of ADIVIMA, the People’s Legal Clinic, as well as the ongoing Chixoy Dam reparation campaigns.

One of the primary accomplishments of both ADIVIMA and Rights Action, among other organizations, has been the development of the Rabinal Achi Community Museum. Besides helping maintain alive the historical memory of the still recent atrocities, the museum also provides a number of other services such as a library, computer lab, and a specific exhibit dedicated to the local Maya Achi culture and its rich traditions.

One of the primary accomplishments of both ADIVIMA and Rights Action, among other organizations, has been the development of the Rabinal Achi Community Museum. Besides helping maintain alive the historical memory of the still recent atrocities, the museum also provides a number of other services such as a library, computer lab, and a specific exhibit dedicated to the local Maya Achi culture and its rich traditions. Mr. Nicolas Chen, a survivor from Rio Negro, often visits the museum where a number of his murdered relatives’ photographs are on display. Here, Mr. Chen caresses the photograph of his daughter, Marta Julia Chen Osorio, where the caption reads: “She was murdered when her gestation period was about to be completed. The soldiers, acting as medics, induced a forced cesarean with machetes. The assailants, who wanted to see how a child grows inside a mother’s womb, accomplished their feat. How is it possible that someone can take the life of defenseless human beings so unjustly?!”

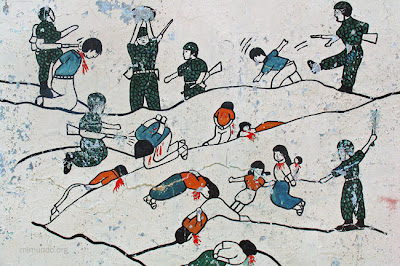

Mr. Nicolas Chen, a survivor from Rio Negro, often visits the museum where a number of his murdered relatives’ photographs are on display. Here, Mr. Chen caresses the photograph of his daughter, Marta Julia Chen Osorio, where the caption reads: “She was murdered when her gestation period was about to be completed. The soldiers, acting as medics, induced a forced cesarean with machetes. The assailants, who wanted to see how a child grows inside a mother’s womb, accomplished their feat. How is it possible that someone can take the life of defenseless human beings so unjustly?!” Another important symbolic achievement in Rabinal has been the construction of several monuments at the municipal cemetery which commemorate the regional victims of the violence during the internal conflict. Each mausoleum displays the names of those killed; some contain actual human remains, and most retell how each massacre took place be it through written form and/or via murals.

Another important symbolic achievement in Rabinal has been the construction of several monuments at the municipal cemetery which commemorate the regional victims of the violence during the internal conflict. Each mausoleum displays the names of those killed; some contain actual human remains, and most retell how each massacre took place be it through written form and/or via murals. This monument, which commemorates the victims of the Agua Fria massacre, reads: “So that our [future] generations may know the truth. Here lay the remains of 97 humble peasants – men, women and children – from the Hamlet of Agua Fria, Uspantan, Quiche, who were brutally burned and massacred by the PAC of Xococ and the Guatemalan Army.”

This monument, which commemorates the victims of the Agua Fria massacre, reads: “So that our [future] generations may know the truth. Here lay the remains of 97 humble peasants – men, women and children – from the Hamlet of Agua Fria, Uspantan, Quiche, who were brutally burned and massacred by the PAC of Xococ and the Guatemalan Army.”Those who survived the aforementioned Rio Negro massacres sought refuge in nearby villages such as Agua Fria. Indicating a clear intention to exterminate completely the population of Rio Negro, the Army in conjunction with the paramilitary group from Xococ, continued to hunt and massacre the survivors of previous mass killings.

Members of the delegation organized by Rights Action, the institution that also financed the construction of the mausoleums, take a stroll through the so-called monument alley in the cemetery of Rabinal.

Members of the delegation organized by Rights Action, the institution that also financed the construction of the mausoleums, take a stroll through the so-called monument alley in the cemetery of Rabinal.Graham Russell explains how the Rabinal case is fundamental in understanding not only the post-war era which Guatemalan experiences today, but also the philosophy and mission of Rights Action: “The vision of our work for global justice, sustainable development and human rights consists in financing community-designed and implemented projects; to follow-up the lead of the local leaders and organizations in determining what their funding and project priorities are, and to organize North-South education trips that focus in on how global institutions, in this case the WB and IDB, often contribute directly to and/or benefit from Human Rights violations, indeed genocide in this case.”

A visit to the Bilingual Community Institute Nueva Esperanza (New Hope), one of Jesus Tecu Osorio’s dreams which have come true, also formed part of the delegation’s itinerary. The school provides its students with an alternative educational curriculum based on group work, tutors instead of teachers, education materials based on historic memory, and provides specialized classes in sustainable agricultural methods.

A visit to the Bilingual Community Institute Nueva Esperanza (New Hope), one of Jesus Tecu Osorio’s dreams which have come true, also formed part of the delegation’s itinerary. The school provides its students with an alternative educational curriculum based on group work, tutors instead of teachers, education materials based on historic memory, and provides specialized classes in sustainable agricultural methods.Tecu Osorio, who managed to finance the school through his Foundation Nueva Esperanza – Rio Negro thanks to a prestigious international human rights award, focuses on the future: “I continually seek projects with new alternatives so that one day all of those affected by the state-sponsored violence will feel satisfied in having some level of academic achievement.” (13)

Fernando Suazo, to the left of Jesus Tecu Osorio and Sandra Cuffe from Rights Action, has participated in some of Guatemala’s largest and most important projects seeking to recuperate historic memory such as The Massacres of Rabinal compilation and the REMHI report. After serving as a catholic priest in the region for more than a decade, time in which Suazo became widely exposed to the severe psychological damage suffered by the general population, he formed in 1996 the Team for Community Studies and Psychosocial Action (ECAP). Such organization operates through two main branches: the investigation of psychosocial phenomena sprouted by the internal conflict, and also the accompaniment of wartime victims now involved in mentally strenuous processes such as exhumations, testimonies, or those recovering from a number of abuses.

Fernando Suazo, to the left of Jesus Tecu Osorio and Sandra Cuffe from Rights Action, has participated in some of Guatemala’s largest and most important projects seeking to recuperate historic memory such as The Massacres of Rabinal compilation and the REMHI report. After serving as a catholic priest in the region for more than a decade, time in which Suazo became widely exposed to the severe psychological damage suffered by the general population, he formed in 1996 the Team for Community Studies and Psychosocial Action (ECAP). Such organization operates through two main branches: the investigation of psychosocial phenomena sprouted by the internal conflict, and also the accompaniment of wartime victims now involved in mentally strenuous processes such as exhumations, testimonies, or those recovering from a number of abuses.Regarding the highly controversial postwar era, Suazo shares his insight: “This transition into times of peace – the formal, written peace – was not well formulated. The general population, who lived under a smashing clout of silence, was not about to negotiate the peace agreements in a whim. This general population continues to be suffocated by silence when the Peace Agreements are signed… The people were muted, full of fear, traumatized. The general public was not involved in any way in the peace process, and hence, the result is what we have now.”

Perhaps the most notable achievement by Rabinal’s activist community with regards to justice, not only at local but national level, has been the conviction of Pedro Gonzales Gomez and two other former PAC members. All three were sentenced to 50 years of jail each having been found guilty of committing atrocious crimes against humanity. Even so, the grueling task of seeking to bring to justice the intellectual actors of these crimes, in particular high ranking officers and the military dictators of the early 1980s, continues to be a process full of corruption, intimidations and impunity.

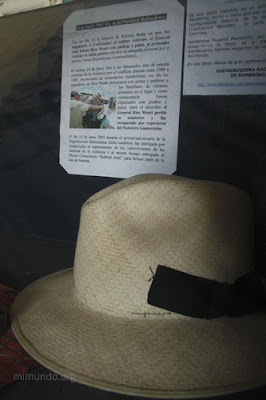

Perhaps the most notable achievement by Rabinal’s activist community with regards to justice, not only at local but national level, has been the conviction of Pedro Gonzales Gomez and two other former PAC members. All three were sentenced to 50 years of jail each having been found guilty of committing atrocious crimes against humanity. Even so, the grueling task of seeking to bring to justice the intellectual actors of these crimes, in particular high ranking officers and the military dictators of the early 1980s, continues to be a process full of corruption, intimidations and impunity.Nevertheless, the symbolic achievements have served as key elements in this chain of events and continue to do so. Inside the Rabinal Achi Community Museum, the Panama hat which once shaded former dictator Efrain Rios Montt serves as a perfect example. On June 14, 2003, Rios Montt, who ruthlessly ruled Guatemala in 1982-83, scheduled a campaign stop in town through his right-wing FRG (Guatemalan Republican Front) Party. Adding insult to injury, the rally coincided with the proper burial of 70 war-time victims recently exhumed from mass graves. The locals couldn’t hold back and stoned Rios Montt out of Rabinal. During the revolt Rios Montt lost his hat which ended up at the community museum, and so giving birth to a local holiday denominated the Day of Rabinalese Dignification, celebrated of course, every June 14.

For more information regarding any of these projects, to organize or participate in an educational delegation to Rabinal, or to provide economic support to the Rabinal Integral Development Program (full proposal available on request), please contact Rights Action at info@rightsaction.org

Versión en español aquí.

2 Ibid. PP. 45-46.

3 Ibid. P. 46.

4 Oj K’aslik / Estamos Vivos: Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica de Rabinal (1944-1996). Publicado por el Museo Comunitario Rabinal Achi. Rabinal, Guatemala. Julio 2003. PP. 29-30.

5 CEH. Op. Cit. P. 47.

6 Ibid. P. 48.

7 Ibid. PP. 48-49.

8 Ibid. P. 49.

9 Ibid. PP. 49-50.

10 CEH. Capitulo Segundo: “Las Violaciones de los Derechos Humanos y los Hechos de violencia”, Parte 2. P. 373.

11 Tecú Osorio, Jesús. Memoria de las Masacres de Río Negro: Recuerdo de mis Padres y Memoria para mis Hijos. Fundación Nueva Esperanza, Río Negro. Rabinal, Guatemala. Reimpresión 2006. P. 101.

12 Continuing the Struggle for Justice and Accountability in Guatemala: Making Reparations a Reality in the Chixoy Dam Case. Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions (COHRE) Mission Report, 2004. PP. 5-6.

13 Tecú Osorio, Jesús. Op. Cit. P. 165.

I met Jesus in Spokane 2001 when He spoike at our univesity.

You should go interview the forensic team in zone 1 that partook in the exhumation and others in the altaverapaz

In 1984 a German agronomist took me to a "resettled" town near Salama and Rabinal which consisted of widows and children from the Chixoy dam area. Interesting to see writings about it decades later.