2008-10. Mining in San Miguel Ixtahuacán: Conflict and Criminalization

November 30, 2008.

Issues: Mining / Criminalization / Society

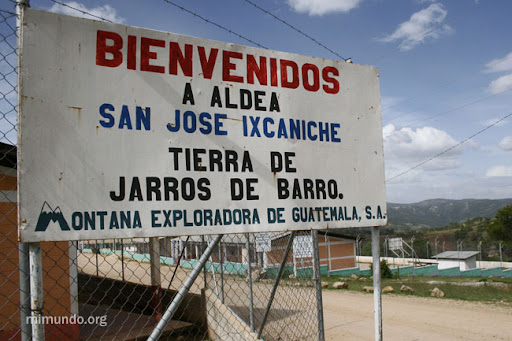

“Experts often consider open-pit mining to be the most destructive industrial activity in terms of environmental depletion, social and cultural impact… In San Miguel Ixtahuacán and Sipakapa, San Marcos, intensive mineral exploitation has already left its mark. Local residents from Agel, Nueva Esperanza and San Jose Ixcaniche remember fondly a gorgeous mountain, famed for its diversity, where one could find various species of birds and butterflies. Today, the only thing left of that place is an enormous crater with contaminated rubble.” (1)

“Experts often consider open-pit mining to be the most destructive industrial activity in terms of environmental depletion, social and cultural impact… In San Miguel Ixtahuacán and Sipakapa, San Marcos, intensive mineral exploitation has already left its mark. Local residents from Agel, Nueva Esperanza and San Jose Ixcaniche remember fondly a gorgeous mountain, famed for its diversity, where one could find various species of birds and butterflies. Today, the only thing left of that place is an enormous crater with contaminated rubble.” (1) “The town of San Miguel Ixtahuacán is no longer the same since the miners arrived. [Montana Exploradora’s] Marlin Mine I has been the local’s apple of discord for the past five years. It has created extreme tension between those who support the project and those who reject it. Serious rifts have been caused even within families.” (2)

“The town of San Miguel Ixtahuacán is no longer the same since the miners arrived. [Montana Exploradora’s] Marlin Mine I has been the local’s apple of discord for the past five years. It has created extreme tension between those who support the project and those who reject it. Serious rifts have been caused even within families.” (2) Towards the end of 2008, in an attempt to improve its image at the national level, Goldcorp (Montana Exploradora’s Canadian-run parent company) has launched an intense propaganda campaign by strategically posting billboards throughout Guatemala City and along principal highways. In this image a gigantic billboard, located just meters outside the main exit of La Aurora international airport, reads: “Development = work = better quality of life. For us at Goldcorp, development is what counts.”

Towards the end of 2008, in an attempt to improve its image at the national level, Goldcorp (Montana Exploradora’s Canadian-run parent company) has launched an intense propaganda campaign by strategically posting billboards throughout Guatemala City and along principal highways. In this image a gigantic billboard, located just meters outside the main exit of La Aurora international airport, reads: “Development = work = better quality of life. For us at Goldcorp, development is what counts.” Delfino Tema, municipal mayor of Sipakapa, explains: “[The mining company] said that nothing negative was going to occur, only progress was to come. But today, the local people are realizing it has been quite the opposite.” (5)In Agel, Irma Leticia Mendez had been living in her home for 13 years when suddenly, in 2006, the walls began to crack: “The company says the fissures are due to the corn grinder I have. But it is due to the explosions.”

Delfino Tema, municipal mayor of Sipakapa, explains: “[The mining company] said that nothing negative was going to occur, only progress was to come. But today, the local people are realizing it has been quite the opposite.” (5)In Agel, Irma Leticia Mendez had been living in her home for 13 years when suddenly, in 2006, the walls began to crack: “The company says the fissures are due to the corn grinder I have. But it is due to the explosions.” Local organizations have reported over 100 homes with structural damage due to the detonations carried out by Montana in their effort to separate rock material and dig tunnels. Throughout these years, Montana has continually denied any responsibility for the damage to the local’s homes. Hence, as a result, the cracked-walls issue has pitted dozens of disgruntled locals against the mine and the few who support it. (6)

Local organizations have reported over 100 homes with structural damage due to the detonations carried out by Montana in their effort to separate rock material and dig tunnels. Throughout these years, Montana has continually denied any responsibility for the damage to the local’s homes. Hence, as a result, the cracked-walls issue has pitted dozens of disgruntled locals against the mine and the few who support it. (6) Throughout the world, communities adjacent to open-pit metal mines suffer a number of the same problems: water shortage, contamination of rivers and underground water reservoirs, respiratory ailments due to the increased dust, deforestation, and contamination of crops and livestock. “When there is agricultural production near a mine, nearby plants and crops absorb the cyanide and heavy metals, which pose a great threat to human health.” (7)

Throughout the world, communities adjacent to open-pit metal mines suffer a number of the same problems: water shortage, contamination of rivers and underground water reservoirs, respiratory ailments due to the increased dust, deforestation, and contamination of crops and livestock. “When there is agricultural production near a mine, nearby plants and crops absorb the cyanide and heavy metals, which pose a great threat to human health.” (7)

“There is also social contamination occurring in our communities,” explains a local resident of Agel who wishes to remain anonymous. “Our own people rise up against us. Those who defend the company have even threatened to kill us. Many strange things have happened since the mine opened. We do not want any more of this.”

“There is also social contamination occurring in our communities,” explains a local resident of Agel who wishes to remain anonymous. “Our own people rise up against us. Those who defend the company have even threatened to kill us. Many strange things have happened since the mine opened. We do not want any more of this.”

Forced disappearances and murders of community members who oppose the industrial project are among these so-called “strange things”. “On June 15, 2007, the decapitated body of Pedro Miguel Cinto, an elderly man who lived in front of the mine’s entrance was found by a child pasturing sheep… He and his family had been active against the mine.” (8)

Forced disappearances and murders of community members who oppose the industrial project are among these so-called “strange things”. “On June 15, 2007, the decapitated body of Pedro Miguel Cinto, an elderly man who lived in front of the mine’s entrance was found by a child pasturing sheep… He and his family had been active against the mine.” (8)

Maria Sebastiana Perez holds a photo of his son, Byron Lionel Bamaca Perez, who disappeared in May 2007 along with her brother-in-law, Marco Tulio Rodriguez. Both men worked as cooks for the mine and disappeared while sent on an errand for the company. “My husband worked for Montana, but he was fired,” explains Mrs. Perez. “So when my son went to ask them [to rehire his father], company workers took him to Quiche… And he never came back. I want the company to leave. They have done enough harm to us.”

“On January 10, 2007, [28 local leaders] approached Montana/Goldcorp’s local offices hoping to open up a dialogue to resolve several of the negative impacts the company’s operations has caused: damages to homes, environmental and water contamination. Local leaders also hoped to renegotiate the pitiful prices the company paid indigenous locals for their land, when 600 families were coerced and forced to sell all of their land to the company. The mine currently extracts massive quantities of gold valued at millions of dollars from these former private lots.” (9)

“On January 10, 2007, [28 local leaders] approached Montana/Goldcorp’s local offices hoping to open up a dialogue to resolve several of the negative impacts the company’s operations has caused: damages to homes, environmental and water contamination. Local leaders also hoped to renegotiate the pitiful prices the company paid indigenous locals for their land, when 600 families were coerced and forced to sell all of their land to the company. The mine currently extracts massive quantities of gold valued at millions of dollars from these former private lots.” (9)

Following the attempt to dialogue with Montana’s directors, an altercation followed between protesters and the company’s private security forces. The squabble broke off the dialogue and gave way to massive protests in which an estimated 600 community members blocked off all access roads to the Mine for over ten days. (10) Montana Exploradora reacted by pressing legal charges against seven local leaders, accusing them of minor injuries, threats, coercion, and instigation to delinquency (all of which carry jail sentences in Guatemala). (11)

Following the attempt to dialogue with Montana’s directors, an altercation followed between protesters and the company’s private security forces. The squabble broke off the dialogue and gave way to massive protests in which an estimated 600 community members blocked off all access roads to the Mine for over ten days. (10) Montana Exploradora reacted by pressing legal charges against seven local leaders, accusing them of minor injuries, threats, coercion, and instigation to delinquency (all of which carry jail sentences in Guatemala). (11)

The trial of the so-called “Goldcorp 7” ended in December 2007, with five of the accused absolved due to lack of evidence. Meanwhile, Fernando Perez and Francisco Bamaca were condemned to house arrest for 2 years and a hefty fine. Their case is currently under appeal. (12)

Francisco Bamaca worked four years for Montana Exploradora in its community relations program and later in the industrial security division. Despite assuring us that he did not participate in the January 10th protest, Francisco Bamaca was one of the seven accused. A month later, in February 2007, National Civil Police (PNC) members, soldiers, and a few masked men (presumably members of Montana’s private security corps), stormed into Mr. Bamaca’s home before dawn and proceeded to terrorize and beat members of his family.

Francisco Bamaca worked four years for Montana Exploradora in its community relations program and later in the industrial security division. Despite assuring us that he did not participate in the January 10th protest, Francisco Bamaca was one of the seven accused. A month later, in February 2007, National Civil Police (PNC) members, soldiers, and a few masked men (presumably members of Montana’s private security corps), stormed into Mr. Bamaca’s home before dawn and proceeded to terrorize and beat members of his family.

“I worry about my family’s future and the wellbeing of my community. But [Montana Exploradora] did not want me to reveal their real intentions,” expresses Francisco Bamaca. “I was very concerned about the tunnels they are digging under the hills and they didn’t want me to say anything. Just because I didn’t agree, they fired, harassed, and prosecuted me.”

“The Marlin Mine in Guatemala, which hopes to produce 250,000 ounces of gold and 4 million ounces of silver annually during its lifetime, has faced continual protests since its inception in 2004.” (13)

“The Marlin Mine in Guatemala, which hopes to produce 250,000 ounces of gold and 4 million ounces of silver annually during its lifetime, has faced continual protests since its inception in 2004.” (13)

Furthermore, “it is widely believed that through this type of judicial processes, the company hopes to criminalize and weaken anti-mining social movements in San Miguel Ixtahuacán while it expands its mining activities in the area.” (14)

The Power Lines Issue and the Eight Women of Agel

Such strategy of criminalizing local resistance leaders has once again been applied this year in San Miguel Ixtahuacán. The trial of the so-called “Goldcorp 7” left deep wounds among the actors involved: the mining company, local community members who support it, and those who oppose its presence. New protests have sprouted and still the company follows its antagonistic patterns by pressing legal charges against the indigenous resistance. Those suffering the consequences now are eight Mayan women who have orders of arrest against them for having cut off the company’s electric supply in June of this year. (15)

Such strategy of criminalizing local resistance leaders has once again been applied this year in San Miguel Ixtahuacán. The trial of the so-called “Goldcorp 7” left deep wounds among the actors involved: the mining company, local community members who support it, and those who oppose its presence. New protests have sprouted and still the company follows its antagonistic patterns by pressing legal charges against the indigenous resistance. Those suffering the consequences now are eight Mayan women who have orders of arrest against them for having cut off the company’s electric supply in June of this year. (15)

In 2005, Montana Exploradora installed high-voltage electric power lines over three communities adjacent to the mine. In some cases, contracts were signed with local people to install and keep the poles within their private property areas. Several local residents, however, have complained about the company’s failure to respect such contracts, or the fact that Montana never even asked some of them for permission before setting up the electric infrastructure. (16)

In 2005, Montana Exploradora installed high-voltage electric power lines over three communities adjacent to the mine. In some cases, contracts were signed with local people to install and keep the poles within their private property areas. Several local residents, however, have complained about the company’s failure to respect such contracts, or the fact that Montana never even asked some of them for permission before setting up the electric infrastructure. (16)

“The posts that support the high-voltage power lines are about to fall on several homes,” an obviously worrisome situation. In addition, “high-voltage electric power lines have a negative effect on human and animal health due to the radiation they emit, which is also a problem for local families,” declares Javier De Leon, a member of the Association for the Integral Development of San Miguel Ixtahuacán (ADISMI). (17)

“The posts that support the high-voltage power lines are about to fall on several homes,” an obviously worrisome situation. In addition, “high-voltage electric power lines have a negative effect on human and animal health due to the radiation they emit, which is also a problem for local families,” declares Javier De Leon, a member of the Association for the Integral Development of San Miguel Ixtahuacán (ADISMI). (17)

Nevertheless, the main problem arising from the power lines dispute has to do with the violations of private property. “The company did not ask me for permission. They simply put them there,” states Gregoria Crisanta Perez, resident of Agel. Goldcorp claims they have a lease agreement with Mrs. Perez since 2004 that allows them to keep the poles in her property. Yet Tim Miller, Goldcorp’s Vice-President of operations in Central and South America, admits he does not know whether Gregoria Perez indeed signed the contract: “I cannot really say exactly who signed it.” (18)

Nevertheless, the main problem arising from the power lines dispute has to do with the violations of private property. “The company did not ask me for permission. They simply put them there,” states Gregoria Crisanta Perez, resident of Agel. Goldcorp claims they have a lease agreement with Mrs. Perez since 2004 that allows them to keep the poles in her property. Yet Tim Miller, Goldcorp’s Vice-President of operations in Central and South America, admits he does not know whether Gregoria Perez indeed signed the contract: “I cannot really say exactly who signed it.” (18)

On June 10, 2008, Mrs. Perez provoked a short circuit on the electric lines which hang above her home, causing a power failure which interrupted the mine’s operations. Soon after, “about 150 residents of several communities from the municipality of San Miguel Ixtahuacán, San Marcos, declared themselves in a permanent state of alert as a way to protest the Marlin Project’s continuing activities” and to provide support for Mrs. Perez. (19)

On June 10, 2008, Mrs. Perez provoked a short circuit on the electric lines which hang above her home, causing a power failure which interrupted the mine’s operations. Soon after, “about 150 residents of several communities from the municipality of San Miguel Ixtahuacán, San Marcos, declared themselves in a permanent state of alert as a way to protest the Marlin Project’s continuing activities” and to provide support for Mrs. Perez. (19)

Three days later, “representatives from the mine arrived along with 35 national police officers and private security guards from the company… As the gathered women did not allow engineers to enter the property, the security forces began to violently threaten the women and children with tear gas. The local women continued their resistance and created a human chain that the police was not able to break.” (20)

Three days later, “representatives from the mine arrived along with 35 national police officers and private security guards from the company… As the gathered women did not allow engineers to enter the property, the security forces began to violently threaten the women and children with tear gas. The local women continued their resistance and created a human chain that the police was not able to break.” (20)

“Perez, a mother of six, said she will not negotiate with the company until they agree to compensate all local families for the damages they have caused.” Montana Exploradora’s response to the protest was similar to how it reacted after the January 2007 altercation: Eight arrest warrants were issued against local women from Agel, including Gregoria Crisanta Perez. (21)

“Perez, a mother of six, said she will not negotiate with the company until they agree to compensate all local families for the damages they have caused.” Montana Exploradora’s response to the protest was similar to how it reacted after the January 2007 altercation: Eight arrest warrants were issued against local women from Agel, including Gregoria Crisanta Perez. (21)

Maria Catalina Perez Hernandez, one of the eight women with detention orders, states: “We are deeply saddened by the mining company’s lies. We are even afraid to walk down our streets due to the problems the mine has brought. A deep division has gripped our community.”

Maria Catalina Perez Hernandez, one of the eight women with detention orders, states: “We are deeply saddened by the mining company’s lies. We are even afraid to walk down our streets due to the problems the mine has brought. A deep division has gripped our community.”

Crisanta Hernandez, also a resident of Agel with a detention order, states: “We are very unhappy because we don’t know what to do. We are desperate and sad because we see that our homes are about to fall on top of us and we have nowhere to go… We don’t want the [mining] company to keep cheating our people and creating problems in our communities. They have issued arrest warrants against us just because we are defending our rights. We haven’t killed anyone. We are decent people.”

Crisanta Hernandez, also a resident of Agel with a detention order, states: “We are very unhappy because we don’t know what to do. We are desperate and sad because we see that our homes are about to fall on top of us and we have nowhere to go… We don’t want the [mining] company to keep cheating our people and creating problems in our communities. They have issued arrest warrants against us just because we are defending our rights. We haven’t killed anyone. We are decent people.”

Patrocinia Mejia Perez, also from Agel and another one of the accused, comments: “I don’t know why the [mining] company comes here to harass us. Why do they come with their police? They should have talked to us. We do not carry guns or machetes, while the PNC officers are heavily armed. How is it possible that the company pits the police against us? Is that how they thank us for selling them our plots of land? They take away the gold, and now they put us in jail… If they had considered us, we wouldn’t have had to rise up. But they did not consider us. We don’t want any Canadians to come and boss us around in our own land! We are native Miguelenses!”

Patrocinia Mejia Perez, also from Agel and another one of the accused, comments: “I don’t know why the [mining] company comes here to harass us. Why do they come with their police? They should have talked to us. We do not carry guns or machetes, while the PNC officers are heavily armed. How is it possible that the company pits the police against us? Is that how they thank us for selling them our plots of land? They take away the gold, and now they put us in jail… If they had considered us, we wouldn’t have had to rise up. But they did not consider us. We don’t want any Canadians to come and boss us around in our own land! We are native Miguelenses!”

“Just as we cannot enter the mining company’s grounds, we do not want anyone entering our property,” states a community member from Agel. “If they decide to enter here, it will be their problem. We will no longer allow them to come and take [mineral] samples from our plots. I will beat them out [of my property] with a stick! I’m sorry, but I don’t want to see the mining company taking more gold from here because we have already seen the consequences. All it does is lead us to jail.”

“Just as we cannot enter the mining company’s grounds, we do not want anyone entering our property,” states a community member from Agel. “If they decide to enter here, it will be their problem. We will no longer allow them to come and take [mineral] samples from our plots. I will beat them out [of my property] with a stick! I’m sorry, but I don’t want to see the mining company taking more gold from here because we have already seen the consequences. All it does is lead us to jail.”

“We are afraid to be put in jail, especially because of our children. There are other neighbors who want to harm us because the mining company gives them jobs or money. But it doesn’t matter. What we want is for [Montana Exploradora] to take away its posts, pay for the damages they have caused, and leave this place,” declares another community member from Agel.

“We are afraid to be put in jail, especially because of our children. There are other neighbors who want to harm us because the mining company gives them jobs or money. But it doesn’t matter. What we want is for [Montana Exploradora] to take away its posts, pay for the damages they have caused, and leave this place,” declares another community member from Agel.

“‘The State has revived its previous discourse (the idea of an ‘internal enemy’) against the political opposition, dissidents, and those who question the status quo’, asserts Claudia Samayoa, social movement activist and philosopher. According to Samayoa’s analysis, there is a clear distinction to the government’s reaction after 2004, when the anti-Free Trade Agreement protests and struggles for community control of natural resources (water, minerals, etc) took place.” (22)

“‘The State has revived its previous discourse (the idea of an ‘internal enemy’) against the political opposition, dissidents, and those who question the status quo’, asserts Claudia Samayoa, social movement activist and philosopher. According to Samayoa’s analysis, there is a clear distinction to the government’s reaction after 2004, when the anti-Free Trade Agreement protests and struggles for community control of natural resources (water, minerals, etc) took place.” (22)

“The repression apparatus, created to forcibly impose natural resource exploitation mega-projects, is once again active in San Marcos. Multinational corporations, the media, the Prosecutor’s Office, and the Guatemalan government under President Álvaro Colóm, carry out in cahoots a campaign of repression through the criminalization of the population. Livingston, San Juan Sacatepequez, Nueva Linda and other communities are vivid examples of the planned and systematic nature of these campaigns.” (23)

“The repression apparatus, created to forcibly impose natural resource exploitation mega-projects, is once again active in San Marcos. Multinational corporations, the media, the Prosecutor’s Office, and the Guatemalan government under President Álvaro Colóm, carry out in cahoots a campaign of repression through the criminalization of the population. Livingston, San Juan Sacatepequez, Nueva Linda and other communities are vivid examples of the planned and systematic nature of these campaigns.” (23)

“Just as it occurred during the internal armed conflict, the criminalization of social and popular struggles is being felt once again in some communities that get organized,” states Wendy Méndez, a member of HIJOS (Sons and Daughters for Identity and Justice, against Forgetfulness and Silence). “During the internal war, women’s and youth organizations, students, and members of the [Catholic] Church who stood up against the repression and the exclusionary government policies which result in poverty, were singled out as enemies. The construction of such a negative image of their struggles allowed for the genocide to occur. If the government, authorities, and business interests maintain such stance in relation to the peoples’ resistance movements, we run the risk of having history repeat itself.” (24)

“Just as it occurred during the internal armed conflict, the criminalization of social and popular struggles is being felt once again in some communities that get organized,” states Wendy Méndez, a member of HIJOS (Sons and Daughters for Identity and Justice, against Forgetfulness and Silence). “During the internal war, women’s and youth organizations, students, and members of the [Catholic] Church who stood up against the repression and the exclusionary government policies which result in poverty, were singled out as enemies. The construction of such a negative image of their struggles allowed for the genocide to occur. If the government, authorities, and business interests maintain such stance in relation to the peoples’ resistance movements, we run the risk of having history repeat itself.” (24)

Video produced by the Collectif Guatemala regarding this case.

For more information regarding Goldcorp’s mining activities in the Western Hemisphere, please download the following Rights Action booklet (in .pdf):

Investing in Conflict, Public Money Private Gain: Goldcorp in the Americas.

Versión en español aquí.

1 Ibañez, Jeovany. Mundo&Motor Magazine, from Prensa Libre. Guatemala.

http://www.mundoymotor.com/No132_0005_10_2008/mym_1089212103021.htm

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 http://chiapas.indymedia.org/display.php3?article_id=159963

(informe_tpp_caso_goldcorp.doc)

7 Oxfam América. La Minería de Metales en Centroamérica: Dolor y Resistencia. San Salvador, El Salvador, 2008. P. 27.

8 Rights Action. Communiqué: “Urgent Action: Crackdown on Local Citizens Opposing Goldcorp’s ‘Marlin’ Mine Escalates in San Marcos, Guatemala.” July 18, 2008.

http://breakingthesilencenet.blogspot.com/2008/07/urgent-actioncrackdown-on-local.html

9 Guatemala News and Information Bureau (GNIB). Communiqué: “Acción Urgente San Miguel Ixtahuacán: criminalización del movimiento social anti-minas”. Berkeley, California. November, 2007. http://www.albedrio.org/htm/otrosdocs/comunicados/gnib-002.htm

10 Comisión Pastoral Paz y Ecología (COPAE); Diocese of San Marcos. “Habitantes de San Miguel Ixtahuacán obstruyeron el paso a la mina Marlin.” El Roble Vigoroso, No. 6. San Marcos, Guatemala. January 25, 2007.

http://www.resistencia-mineria.org/espanol/?q=node/35

11 Op. Cit. GNIB.

12 COPAE. Communiqué: “Comunicado COPAE ante la condena de dos líderes comunitarios de San Miguel Ixtahuacán”. San Marcos, Guatemala. December 14, 2007.

http://www.noalamina.org/mineria-argentina-articulo997.html

13 http://www.noalamina.org/mineria-argentina-articulo1427.html

14 GNIB. Communiqué: “Acción Urgente San Miguel Ixtahuacán: criminalización del movimiento social anti-minas”. Berkeley, California. November, 2007.

http://www.albedrio.org/htm/otrosdocs/comunicados/gnib-002.htm

15 Op. Cit. Rights Action.

16 Ibid.

17 Flores, Ligia. “Pobladores llevan una semana en protesta pacífica. Resistencia contra minería en Ixtahuacán, San Marcos.” Diario La Hora. Guatemala, June 17, 2008.

http://www.lahora.com.gt/notas.php?key=32183&fch=2008-06-17

18 Law, Bill. “Unease over Guatemalan gold rush”. BBC. August 21, 2008.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/crossing_continents/7569810.stm

19 Op. Cit. Flores.

20 http://chiapas.indymedia.org/local/webcast/uploads/memorial_de_denuncia_tpp.doc

21 http://www.noalamina.org/mineria-argentina-articulo1427.html

22 Cabanas, Andrés. “Criminalización de la lucha social en Guatemala”. Memorial de Guatemala No. 80. May 3, 2007. http://www.revistapueblos.org/spip.php?article577

23 Bloque Antiimperialista. Communiqué: “La rebeldía, una condición del pueblo de San Marcos.” Guatemala, August 2008. http://chiapas.indymedia.org/display.php3?article_id=158225

24 CERIGUA. “Vuelve la criminalización de la lucha social.” Guatemala. October 11, 2008.

http://cerigua.info/portal/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=4667&Itemid=31